|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Siri vs. Windows Speech Recognitionby Laura Frädrich, BA and Dimitra Anastasiou, PhDLanguages and Literary Studies, University of Bremen, Germany | |

|

1. Introduction

Nevertheless, there are many aspects of communication that constitute a challenge for those systems, which we do not realize when interacting with humans. For instance, when talking to someone in a noisy environment with many other people also talking in the background, it is normally no problem for us humans to concentrate on the person before us, and extract and correctly process his/her words out of all the acoustic signals. Additionally, it does not make a difference to us if the interlocutor speaks with a slight accent. We can effortlessly understand people we have never talked to before and discuss a broad variety of topics in a a formal or colloquial style. This paper shows how speech recognition programs can be used by comparing two systems: Microsoft Windows Speech Recognition (henceforth WSR) and Apple’s new feature on the iPhone 4S, Siri.

This paper is laid out as follows: In section 2 we give an overview of speech recognition in general (history, definition, classification, challenges). In

sections 3 and 4, those general ideas will be applied to WSR and Siri respectively, to give an objective impression of the systems that will be evaluated

later on. After that we describe our methodology of testing the two systems with a focus on user-friendliness and usability on the basis of a tested text,

which can be found in the Appendix. In section 7 a conclusion sums up our evaluation.

Automatic speech recognition (also called “computer speech recognition” or “speech-to-text”) can be described as “converting the speech waveform (…) into a sequence of words” (Mitkov, 2004: 305). Today mostly statistical models are used in speech recognition. Generally, these models aim at finding the most probable string of words given a specific acoustic signal. While there is no universal speech recognition system yet that works satisfactorily in every conceivable situation, there are various systems, which differ in their usability for diverse purposes. First, a distinction should be made between speaker-dependent, speaker-independent, and speaker-adaptive systems. Speaker-dependent programs recognize only the speech of users that they have been trained on, whereas speaker-independent systems also work with “unknown” users. Speaker-adaptive systems are a special kind of speaker-independent ones: though they generally recognize every speaker, their performance can be improved by adapting to certain users through training. This can be done either beforehand in a very short training phase (in contrast, speaker-dependent programs require hours of training) or via "on the job training" while using the system. A second distinction can be made by describing the size of the stored vocabulary, which can either be small (for example a two-word vocabulary for a yes/no detection), medium (1,000 to 3,000 words), or large (approximately 65,000 words) (Mitkov, 2004: 318). Another way of distinguishing speech recognition systems is based on the type of processable utterances. Isolated word recognizers only work on single words, e.g. short commands, surrounded by pauses. On the next level, keyword spotting systems are able to extract specified keywords out of a spoken text. Another, harder, step is recognizing a sequence of connected words selected from a small number of distinct words that can be used (for instance the so-called “digits task”: recognizing telephone or credit card numbers spoken in a fluent way) (Pfister & Kaufmann, 2008: 290-292). Processing continuous speech is surely the hardest task, since phrases need to be segmented; the vocabulary size in these speech recognition systems is usually quite large. Within the task of continuous speech recognition, Jurafsky & Martin (2009) distinguish between recognizing read speech (used when a human dictates to a machine) and conversational speech (the transcription of a conversation between two humans). Last but not least, speech recognition should not to be confused with speaker recognition, as the latter aims at identifying the speaking person instead of transcribing what is being said.

An introduction to the relationship between speech technology and computational linguistics is given by Cartensen et al. (2010), while Schroeder (2004)

describes the process of recognition-compression-synthesis.

One of the main factors that influence the performance of a system is background noise. Speech recognition systems usually work best under laboratory conditions: a quiet room with only one person speaking into a microphone. Since in reality this is often not the case (other people talking in the background, music, motor noises etc.) this represents a major challenge for speech recognition systems. What also needs to be considered is the fact that no one usually says one thing twice in exactly the same way. In addition, the speech signal is always influenced by gender, age, and mental state a person is currently in, in addition to many other factors. Thus a speech recognition system needs to know which factors are distinctive and which do not have to be considered, and possibly be customized.

Specific challenges appear based on the purpose a speech recognition system is designed for. For instance, a continuous speech recognizer has to segment

the audio signal into pieces first that can be processed afterwards. It should also be required to deal with expletives and noises a person produces

besides speaking (e.g. chuckling, breathing, clearing his/her throat etc.).

The idea of creating “speaking” machines has been inspiring people for about 130 years. What began not as a means of interaction between human and computer, but only as a way of producing speech in 1880, resulted in what could be called the first automatic speech recognizer in the early 1950s. Three researchers of the Bell Telephone Laboratories in the USA developed a system that was able to recognize isolated digits from 0 to 9 of a single speaker by best-matching them against speaker-dependent standard digits patterns (compare Juang & Rabiner, 2004). Soon similar systems for isolated one-syllable-words followed. Following this concept, two decades passed without any considerable improvements in respect to continuous speech and the ability of recognizing various speakers until a breakthrough was made. In 1971 the U.S. defense research agency ARPA sponsored a research initiative in the field. Five years later only one system met the requirements: Pennsylvanian Carnegie Mellon University’s “Harpy” that was able to satisfactorily recognize connected speech using a vocabulary of over 1,000 words. Its performance was still very slow; a four-second sentence would have taken more than five minutes. Nonetheless, the foundation for future success was laid, as it was the first model to use hidden Markov models and statistical modeling. Those models are still considered working best nowadays, and therefore they are mostly used in contemporary speech recognition. Moreover, today they are also supported by semantic models (Juang & Rabiner, 2004).

Research continues to be conducted with the aim to improve accuracy, enlarge the vocabulary, and reduce the procession time. Additionally, many researchers

have turned to include speech synthesis and multimodal systems that allow various input methods (apart from speech, also gestures, haptics etc.) in order

to develop multimodal dialog systems.

Windows Speech Recognition is a program developed by the Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft itself advertises its tool on its website as follows: “Give your wrists and neck a break with Speech Recognition (…), which lets you talk your way through windows and programs or compose an e-mail, no keyboard required. Say "Show Desktop" to minimize open windows. Or say "Open Excel" to launch Microsoft Excel. Type less and do more with the natural power of your voice”. By standard it is included in the Windows operating systems Windows Vista and Windows 7, but users of earlier versions (at least Windows XP) can download WSR for free from the Internet. We used Windows Vista (version 8.0) to test the WSR system. Applying the categories introduced above, WSR can probably be described as a speaker-adaptive, large-vocabulary continuous speech recognizer. It can cope with a variety of tasks: transcribing dictated texts, formatting these texts, opening programs or websites, filling in forms, etc. Generally, the way a user can request these tasks to be done can be divided in two groups: telling the system specified commands and dictating text. The commands need to be chosen from a list of possible commands. If one wants to call up something, but does not know the specific command for carrying out the underlying function, he or she can always tell the system “Show numbers”. This command overlays every clickable item (files, buttons etc.) on the whole screen with numbers. Now the user can choose the number of the preferred item, what works as if he/she had (double-) clicked on it with a mouse.

The WSR application can be found under “Systemsteuerung/Control Panel” > “Erleichterte Bedienung/Ease of Access” >

“Spracherkennungsoptionen/Speech Recognition Options”. Now users can decide what they want to do: starting the speech recognition, configuring

the microphone, running a tutorial, or training the program to improve its performance. Users can also open a list of the most common commands (the

“speech reference card”) that can be used. Additionally, a link to the Microsoft website is provided for further information.

Before starting the speech recognition for the first time, users need to run the tutorial. This does not only help them on how to use the program, but also helps the system to get used to their voice. This lasts about 30 minutes. Further information on the tutorial will be provided below when describing the process of working with WSR. After having run the tutorial once, users can directly start WSR whenever they want to by returning to the Speech Recognition Options panel and double-clicking on “Start Speech Recognition”. This opens a small oval panel (see Image 1 below). The color of the round button with the microphone icon on the left and the black box in the middle indicate the state in which the system is currently in. The field between button and black box shows whether there is an acoustic input.

When the button is blue and “Zuhören” (“Listening”) appears in the black box, users can start speaking. While a command is carried out, that command is shown in the box. The button turns yellow and the question “Wie bitte?” (“Pardon?”) appears when the utterance does not match any of the possible commands. A grey-blue button with “Im Ruhezustand” (“Sleeping”) signifies that the system is not listening and a grey button with “Aus/Off“ appears, if the system is deactivated (e.g. because no microphone is connected).

The essential commands for using it are the following: “Jetzt Zuhören” (“Listen now”) makes WSR ready to recognise and

“Nicht mehr Zuhören” (“Stop listening”) returns it into the sleeping mode.

As already stated above, Windows Speech Recognition is only available to users of Windows Vista and Windows 7. Furthermore WSR supports the following six

languages: English (British English and American English), French, German, Spanish, Japanese and Chinese (Traditional and Simplified Chinese). Users of

other languages have to change their operating system to one of those, as WSR only works, if its language setting matches the language of the operating

system. Apart from that, it hs no further limitations.

According to Apple Inc., Siri (abbreviation of “Speech Interpretation and Recognition Interface”) is “the intelligent personal assistant that helps you get things done just by asking”. It is a built-in feature of the latest iPhone 4S, which was launched in October 2011. On 4 June 2012 it was announced that the whole Siri voice assistant (iOS 6) and not only the voice dictation will be brought to the iPad in autumn 2012. Siri was originally developed as an application for every iPhone generation by Siri Inc. This company was acquired by Apple in 2010. One year later, after improving and implementing it in the iPhone 4S, the Siri app was removed from the App Store. According to Apple, Siri is a mobile software agent that helps users operate their iPhone and its applications by recognizing their utterances directed at it in natural speech. Because of this, it can be described in the same way as WSR: it is a large-vocabulary continuous speech recognizer, which also adapts to the speaker as can be seen below. Unlike Windows Speech Recognition, users do not need to formulate their requests in a predefined way. Instead they can either express them as questions in order to gain information or as commands for working with an application (e.g. for scheduling an appointment or dictating an e-mail). Questions are normally answered by carrying out a web search. When more information is needed to complete a request, Siri asks the user for it. In contrast to WSR, users cannot tell Siri to open a specific application, but only to use it. For example, users can instruct it to send an e-mail with a certain content to someone, but not tell it to open the e-mail application and then type it themselves.

Apple claims Siri’s performance is improved the more one uses it, as it gets used to the accent and other characteristics of the users’ voice.

Siri can be used right away without running a tutorial or having to set it up. The user presses the “Home button” till hearing two quick beeps. The display turns black and the question “Wie kann ich behilflich sein?” (“What can I help you with?) appears. Additionally, a round icon appears with a microphone on it (similar to the icon on Windows Speech Recognition panel). This icon needs to be tapped before and optionally also after speaking (which is always accompanied by two quick beeps). Immediately it lights up in the middle showing that Siri is ready to be spoken to and gets circled by light when the speech is being processed. Then what has been said is displayed together with a response, which is in addition articulated aloud by a female sounding voice (although Siri has a male voice in the U.K. and in France).

Another way of starting the speech recognition works by simply holding the mobile phone to the ear. After hearing the typical two beeps, users can start

talking.

The dictation function is supported in any application that has a keyboard, for example in the notes or the e-mail app. The microphone icon that again needs to be tapped can be found on the left of the space bar. After touching the microphone icon, the keyboard turns gray while the icon gets bigger. A “Fertig” (“done”) button appears that needs to be tapped after speaking. While processing the speech, three purple circles can be seen in the place where the transcribed speech appears after it.

Since the virtual assistant actually goes beyond speech recognition and intertwines with speech synthesis and other aspects of speech processing, we will

concentrate more on the dictation function in testing and evaluating the two systems.

As the iPhone itself is a commercial product, there are no extra features on Siri that have to be paid for. Nevertheless there are some tool limitations for users outside the United States. For example, it cannot look for maps and traffic data outside the USA. Something that should also be noted is that an Internet connection is required, because Siri communicates with Apple’s data centers to recognize what has been said. A third restrictive aspect is that Siri is only available in a few languages: English (with British, American or Australian accent), French, and German.

For now Siri only works on the iPhone 4S. As Apple claims Siri to be only a beta version that still needs improvement, only the dictating function will be

available on the third generation iPad while the question answering interface will not.

In the following sections we describe the process of working with each of the two systems and compare them in terms of user friendliness, usability, and

performance.

We chose a headset, since that was the recommended type for getting the best performance. The microphone needed to be positioned correctly and then its volume to be adjusted by reading some sentences into it. The tutorial started automatically directly thereafter. It lasted approximately 30 minutes and introduced the basic functions of WSR: how to activate and deactivate it, using the dictating function, commanding and generally using Windows. The tutorial is designed rather neatly with a well-structured Graphical User Interface (GUI). Every function is explained first, followed by some exercises the user needs to complete before being able to move to the next function. While learning how to use WRS, the program also learns to adapt to the speaking style and vocabulary of the user by compiling a speech profile. On the one hand, the didactic concept and the training approach are clearly understandable and visible in the tutorial (repeating commands over and over again surely help users to remember them later on), but, on the other hand, at some point it actually gets a bit annoying. To keep it comparable with Apple’s dictation function, we decided not to run the training program, which would have required reading a given text to it at a particular pace. WSR recommends printing out the speech reference card (overview of the most common commands) to have a list at hand where to look for specific commands, if one does not remember some. But as we can always ask the system “Was kann ich sagen?” (“What can I say?”) to call up the speech reference card, we do not think that this is really necessary. Actually, users can say anything that starts with “What can I...”—even ungrammatical series of words call up the commando overview, though at times the program additionally indicates that it did not understand the utterance. Apart from that, the commands are relatively intuitive and can easily be remembered. If users use the correct commands, they are recognized nearly every time and it feels quite relaxing to simply dictate a text instead of typing it. For dictating a text, we opened Microsoft Word and started reading a text, of course also voicing punctuation marks. In order to format it, the commands must be kept in mind.

Whenever WSR got us wrong, we said “Das hier löschen” (“Delete that”) to delete the last few words as we had learned in the

tutorial. “Korrigiere X” (“Correct X”) makes it open another window with a list of alternative suggestions for word X. If the

intended word is not included, users have the option to spell it letter by letter, otherwise choose it and confirm their choice with “OK”.

As there is the virtual assistant on the iPhone that ensures that all the relevant information needed to meet the users’ request is available, no predefined commands are necessary. So, we could start right away without running a tutorial beforehand. Before trying out the dictation function, we decided to talk a bit to Siri to get acquainted with it. The speech recognition worked quite well, as most of the time our utterances were displayed correctly. Nevertheless Siri apparently needed some time to get used to our voice, as the first four or five requests were not recognized correctly. In such a case, a web search for the misunderstood words is suggested, which in our opinion, is a rather intelligent way of dealing with the problem. We preferred starting Siri by pressing the Home button. In that way we could immediately see if our utterance was recognized as we wanted it to be. The most comfortable holding position was about 15 cm away from the face. We could talk to it at a normal volume and a natural manner—again no robotic, “Dalek”-like speech was necessary as one might have thought. As stated above, we will concentrate more on the dictation function now. It can be used in any application where there is a keyboard. We tried it out using the “Notizen” (“notes”) program, as this seemed to be the most comparable to Microsoft Word. Without an introduction before, we had no idea what to expect, especially regarding special characters and formatting the text. However, dictating turned out to be quite an easy task on the iPhone. We had to do nothing but speak the words, again also voicing the punctuation. New lines or words in capital letters we commanded in the right way intuitively, simply by announcing them: “Neuer Absatz” (“New line”) starts a new line, while “Großbuchstaben X” (“Capital letters X”) returns word X in capital letters. Even smileys can be dictated—for instance “Zwinkerndes Gesicht” (“Winking face”) returns “;-)”. Especially after already having tried speech recognition with WSR, we had no problem with those special cases as the commands are actually quite similar. We found out that around 50 words can be processed at once, after that the program stops listening automatically. In addition, if it cannot transcribe the utterance, it just acts as if nothing at all had been said.

When it did not understand our command the first time, we thought that we could correct the error by saying something like “correct X” or

“delete X”—but nothing happened apart from that these words being transcribed. So we had to correct it through typing, which was quite a

disappointment, since everything else had worked out that well.

For assessing the performance of the two systems on the basis of a dictated text, we chose the first half of an online article of the local newspaper “Weser-Kurier” published on 12 February 2012: “Schüler versuchen sich als Warentester”. The chosen part has a length of 604 words and presents the projects of three different groups of students who compete in “Jugend testet” (“Youth is testing”). We selected this text, as it contains a decent amount of “challenges”, such as named entities (proper names and companies), citations, percentages, a lot of hyphens, and digits.

Regarding the formatting, we will not include anything other than new lines since the “Notizen” app apparently does not support different font

sizes or designs.

As we already have a subjective impression of how both systems perform, we applied objective criteria to evaluate their performance on the test text. We

compared word error rate and sentence error rate, as well as the time the systems need to transcribe the text. The word error rate was defined as the

number of insertions (words that were not dictated but appear additionally), substitutions (replacements of one word by another one) and deletions (missed

words) in the transcription in relation to the total number of words in the original text. On the sentence level the sentence error rate describes the

amount of sentences with at least one incorrect word in relation to the total number of sentences (see Jurafsky & Martin, 2009). Of course, this

implies that we had to dictate the text without correcting anything. The time was assessed from the moment we started dictating until we read the last

word. In contrast to what could be assumed, this is dependent not only on our dictation pace, since we always had to wait for the program to be ready

before going on.

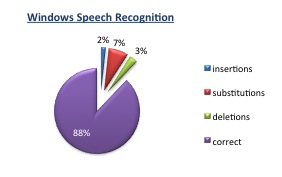

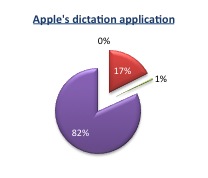

The word error rate of Windows Speech Recognition was 12.09% and its sentence error rate 70.73%. It needed a total time of 9 minutes and 15 seconds for the transcription of the tested data. Apple’s program reached a word error rate of 18.21% and a sentence error rate of 85.37% while transcribing for 18 minutes. The table below shows the proportional distribution of the different errors (insertions, substitutions, and deletions). While Apple’s system nearly only substitutes words by different ones when making a mistake, WSR also deletes and inserts words approximately half of the time. There were also some spelling mistakes: words written as two words instead of one, with a capital letter instead of a lower-case one or with “ß” instead of “ss”. Although we marked them in the transcription, we did not include them in the evaluation.

Image 3: Proportional distribution of errors

What can be inferred directly is that WSR performs better in every respect: it returns lower error rates, while additionally working remarkably faster than the iPhone application. The much longer processing time in Siri is probably related to the fact that it communicates with Apple’s data centers to recognize the speech, a process that just does not work as fast as processing the speech directly on the computer as WSR does it. We can think of two influencing factors that could have affected these results. First, WSR started with an advantage, as it already had the tutorial to adapt to my voice. But since Apple decided not to implement a similar program, they must have trusted that it would work satisfyingly without it. Second, we tested the iPhone of someone else, i.e. Siri was not trained on our voice, which could have affected the performance. Nevertheless, this cannot count as an argument, as the iPhone’s owner had never used this application before. Actually, it seems a bit disappointing that the iPhone only got 6 sentences out of 41 completely right. It is still claimed to be only a beta version, while WSR was released four and a half years ago. While Apple’s speech recognition more often substituted words—sometimes nearly whole sentences, which changed the context significantly—it performed better regarding the deletion of words and punctuation marks. WSR also did not always receive the command for quotation marks (“Anführungszeichen unten/oben”) as a command and instead transcribed it. When using the alternative command “Gänsefüßchen unten/oben” it never failed. Other “special cases” worked perfectly well in both programs: percentages were immediately converted into percentage signs, numbers were transcribed as digits (e.g. “60” instead of “sixty”), “degree” was transformed into “°”. What did not function that well were proper names. The iPhone turned “Jannik” sometimes into “Jan ne” other times into “Jany” or “ja ne”, the last one indicating that it did not even receive this word as a name. Generally, we assume that one would get the overall meaning of the tested text by reading the transcription of one or the other system. The correct details are rather impossible to understand (though again that is easier in the WSR transcription) as sometimes nearly whole sentences are changed, which also changes the content in a quite funny way. A nice example for this provides one sentence in the iPhone transcription, which lists the results a group of students got when testing the quality of crisps: “bei den Tierschützern [waren] durchschnittlich nur 45 % high und 55 % erbrochen” (roughly: “regarding the animal rights activists on average only 45% were high and 55% were thrown up”). The confusion here is the part participle, which should have been “zerbrochen” (broken) instead of “erbrochen” (thrown up). So the transcribed data definitely needs a lot of proofreading.

Just to be able to judge the processing time of the systems, we also measured the time we would have needed to type the article using the touch-typing

method. With only a few typos we needed 18 minutes, the same amount of time the iPhone needed for that task.

In this paper we tested the Windows and the Siri speech recognition systems by dictating a text of 604 words. We drew the conclusion that the Windows system performed better, as it had lower word and sentence error rates than Siri. Depending on the task that users want to perform, both Windows Speech Recognition and Siri are appropriate. On one hand, people who want to dictate whole texts—for instance a journalist driving to her office after an interview with a politician and yet having her head full of ideas of how to formulate the article—should use WSR rather than Apple’s program as the possibility to correct words is really important for such a task. In that case, the journalist definitely needs a good headset to speak into, because the noises from inside and outside the car will probably constitute a problem. On the other hand, people who feel disturbed by having to speak into a microphone should use the iPhone for speech recognition. As users do not have to open the mail program before in order to dictate a message, this is also quite useful when being on the way to someplace without having their hands free. Another important aspect is that Siri also reads out everything aloud, so users do not have to look at the display when actually their attention should be on the road.

To sum up, both systems work fairly well without the speaker having to talk in a robot-like way. When comparing only the dictation function, Windows Speech

Recognition is better than Siri. Nevertheless, it is a bit constrained by predefined commands, while Apple’s dictation function works intuitively

without having to remember specific commands, which gives the user the impression of being able to do anything.

Juang, B.H. & Rabiner, L.R. (2004). Automatic Speech Recognition—A Brief History of the Technology Development. [online], available at: http://my.fit.edu/~vkepuska/ece5526/ASRHistory-Juang+Rabiner.pdf [09.03.12] Jurafsky, D. & Martin, J.H. (2009).Speech and Language Processing. An Introduction to Natural Language Processing, Computational Linguistics, and Speech Recognition. Prentice Hall. (2 nd Edition). Carstensen, K.-U., Ebert, C., Ebert, C., Jekat, S., Langer, H., and Klabunde, R. (Eds.) (2010). Computerlinguistik und Sprachtechnologie. Eine Einführung. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag. Mitkov, R. (2004). The Oxford Handbook of Computational Linguistics. Oxford University Press. Pfister, B. & Kaufmann, T. (2008). Sprachverarbeitung. Grundlagen und Methoden der Sprachsynthese und Spracherkennung. Springer-Verlag.

Schroeder, M. R. (2004). Computer Speech. Recognition—Compression—Synthesis. Springer-Verlag. (2nd Edition).

http://www.apple.com/iphone/features/siri-faq.html , [13.03.12] www.backpain.org.uk/NewsListProductCats.asp , [14.03.12] http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/Speech_Recognition , [13.03.12] www.macstories.net/news/there-are-some-siri-limitations-outside-the-us , [13.03.12] http://www.microsoft.com/en-us/Tellme/consumers/default.aspx#tab=pc , [12.03.12] http://www.microsoft.com/enable/products/windowsvista/speech.aspx , [12.03.12] http://9to5mac.com/2012/06/04/apple-to-bring-full-siri-voice-assistant-to-the-ipad-with-ios-6-mockup-and-details/ , [06.06.12] 10. Appendix 10.1 Original newspaper article

Schüler versuchen sich als Warentester Von Britta Schlesselmann Bremen. Was die Stiftung Warentest im Großen macht, können Jugendliche auch im Kleinen versuchen: Beim Wettbewerb „Jugend testet“ nehmen sie Produkte des täglichen Lebens unter die Lupe. Ihre Testobjekte wählen sie selbst aus—und sie kommen zu interessanten Resultaten. Socken „Wir wollten ein Alltagsprodukt testen“, sagt Jannik Kremers. Gemeinsam mit anderen Zwölftklässlern der Schule an der Grenzstraße entschied er sich für das Testobjekt Socken. Vor dem eigentlichen Test starteten die Schüler eine Umfrage in der Innenstadt: Passanten wurden nach ihren bevorzugten Modellen und ihren Ansprüchen gefragt. „Wir haben uns schließlich für Tennissocken entschieden“, so Jannik Kremers. Untersucht wurden Socken bekannter Hersteller wie Nike, Puma, Adidas und der Karstadt-Eigenmarke Alex. Dabei entwickelten die Schüler einen eigenwilligen Belastungstest: Sie untersuchten die Reißfestigkeit, indem sie Schmirgelpapier an einem Fahrradreifen befestigten, die Socke darunter legten und die Umdrehungen zählten, bis die Socke kaputt war. Die Sportsocke von Puma schaffte ganze 58 Umdrehungen—mehr als jede andere. In einem anderen Versuch untersuchten die Jugendlichen die Formstabilität: Die Socken wurden mehrere Tage über Jumbo-Tassen gestülpt oder mit Gewichten bestückt. „Danach haben wir die Socken gemessen, um festzustellen wie stark sie ausgeleiert waren“, erläutert Jannik Kremers. Er und seine Klassenkameraden testeten außerdem den Tragekomfort—mit verbundenen Augen, damit keiner die Marke sehen kann. Andere Kriterien waren, wie schnell eine Socke fusselt, trocknet und Schweiß aufnimmt. Klarer Sieger: Puma mit 85 von 100 möglichen Punkten. Kartoffelchips Etwas, was viele Jugendliche mindestens so häufig kaufen wie Socken, sind Kartoffelchips. Egal, welche Geschmacksrichtung: Immer bleibt eine Restmenge in der Tüte und landet schließlich im Müll oder zwischen Sofakissen. Doch wie viele Chips sind das eigentlich? Simon Steffens, Lionel Heilmann und Daniel Regenbrecht haben untersucht, wie viele Chips bei einer Menge von 175 Gramm in einer Tüte zerkrümelt sind. Dabei haben sie festgelegt: „Zerkrümelt sind Chips, die durch ein Sieb mit zwei Zentimeter großen Löchern fallen", erläutert der 13-jährige Daniel. Ein passendes Sieb baute er mit seinen Klassenkameraden aus einem Schuhkarton und Drähten. Für ihren Test haben die Schüler des Kippenberg-Gymnasiums Chips im Supermarkt gekauft und vorsichtig transportiert. In ihrem Testlabor landeten jeweils acht Chipstüten der Marken Funny-frisch und Chio—in den Geschmacksrichtungen Paprika und Chili. Nach dem Wiegen der Krümel und der übrigen Chips stand fest: „Bei Funny-frisch waren durchschnittlich 66 Prozent der Chips heil und 34 Prozent zerbrochen, bei den Chio-Chips waren durchschnittlich nur 45 Prozent heil und 55 Prozent zerbrochen.“ Aufgegessen haben die Neuntklässler übrigens den Inhalt aller 16 Test-Tüten—bis auf den letzten Krümel. Tiefkühlpizza Um ein weiteres kulinarisches Thema hat sich eine Gruppe der St.-Johannis-Schule bemüht: Tiefkühlpizza. Untersucht wurden sowohl Markenprodukte von Wagner oder Ristorante als auch Discounter-Pizzen von Lidl, Penny und die Rewe-Hausmarke. Die Zehntklässler teilten die Salami-Pizzen in kleine Stücke, damit alle Schüler und Schülerinnen Geschmack und Geruch beurteilen konnten. „Dabei hat sich gezeigt, dass die Pizza von Lidl sehr gut ankam“, hat Bernward Neugebauer beobachtet. Geschmacklich bewerteten die Tester die Markenprodukte eher schlechter. Ein weiteres Kriterium war die Auftauzeit: Die Schüler gingen davon aus, dass ein Einkauf rund 30 Minuten dauert. Nach dieser Zeit haben sie die Temperatur bei allen Pizzen gemessen und festgestellt, dass sie in jedem Fall über null Grad lag—das heißt, dass man die Pizzen nicht wieder einfrieren sondern sofort zubereiten sollte. Ein anderer Test untersuchte die Abkühlzeit. Bernward Neugebauer: „Wir finden Pizzen unter 30 Grad ungenießbar, daher haben wir auch diesen Aspekt untersucht.“ In dieser Kategorie hätten die Markenprodukte am längsten die Wärme gehalten. Am wenigsten überzeugte die Schüler die Penny-Hausmarke: Der Teig sei ungleichmäßig dick, die Salamischeiben lagen alle auf einer Pizza-Ecke—und auch Geschmack und Geruch seien nicht ansprechend, urteilen die Zehntklässler. 10.2 Transcription by Windows Speech Recognition(Correctly transcribed words that are written in two words instead of one, with a capital letter instead of a small one or with ß instead of ss are underlined.) Schüler versuchen sich als waren Testa ( Von Britta Schlesselmann Bremen. Was die Stiftung Warentest im Großen macht, können Jugendliche auch im Kleinen versuchen: beim Wettbewerb Anführungszeichen unten Jugendtestat Anführungszeichen oben nehmen Sie Produkte des täglichen Lebens unter die Lupe. Ihre Testobjekte wählen sie selbst aus-und sie kommen zu interessanten Resultaten. Socken „Wir wollten ein Alltagsprodukt testen“, sagt Jannik Kremers. Gemeinsam mit anderen zwölf Wislander Schule an der Grenzstraße entschied er sich für das Testobjekt Socken. Vor dem eigentlichen Test starteten die Schüler eine Umfrage in der Innenstadt: Passanten wurden nach ihrem bevorzugten Modellen und Ihren Ansprüchen gefragt. „Wir haben uns schließlich für Tennissocken entschieden“, so Jannik Kremers. Untersucht wurden so ein bekannter Hersteller wie geneigt, Puma, Adidas und der Karstadt Eigenmarke Alex. Dabei entwickelten die Schüler einen eigenwilligen Belastungstest: Sie untersuchten die Reißfestigkeit, indem sie Schmirgelpapier an einem Fahrradreifen befestigten, die Sache darunter legten und die Umdrehungen zählten, bis die Socke kaputt war. Die Sportsocke von Puma schaffte ganze 58 Umdrehungen-mehr als jeder andere. In einem anderen Versuch untersuchten die Jugendlichen die Formstabilität: die Sachen wurden mehrere Tage über die OmU Tassen gestülpt oder mit Gewichten bestückt. „Danach haben wir dieser angemessen, um festzustellen wie stark sie ausgelagert waren“, erläutert Jannik Kremers. Er und seine Klassenkameraden testeten außerdem den Tragekomfort—mit verbundenen Augen, damit keiner DMark gesehen kann. Andere Kriterien waren, wie schnell eine Sorge Voß Welt, trocknet und Schweiß aufnimmt. Klarer Sieger: Puma mit 85 von 100 möglichen Punkten. Cato für Jobs Etwas, was viele Jugendliche mindestens so häufig kaufen wie Socken, sind Kartoffelchips. Egal, welche Geschmacksrichtung: immer bleibt eine Restmenge in der Tüte und landet schließlich im Bälle oder zwischen Sofakissen. Doch wie viele Chips sind das eigentlich? Simon Steffens, Lionel Heilmann und Daniel Regen Brecht haben untersucht, wie viele Chips bei einer Menge von 175 g in einer Tüte zur Krim alt sind. Dabei haben sich festgelegt: „Zerkrümelt sind Ships, die durch ein Sieb mit 2 cm große Löchern Verein“, erläutert der dreizehnjährige Daniel. Ein passendes Sieb baute er mit seinen Klassenkameraden aus einem Schuhkarton und drehten. Für ihren Test haben die Schüler des Kippenberg Gymnasiums Chips in allem im Supermarkt gekauft und vorsichtig transportiert. In ihrem Testlabor landeten jeweils acht Chipstüten der Marken Pfanni frisch und Schirow-in den Geschmacksrichtungen Paprika und Schily. Nach dem Wiegen der Grüne und der übrigen Chips stand fest: Anführungszeichen unten bei Pfanni frisch waren durchschnittlich 66% der Chips heil und 94% zerbrochen, bei den Schirmchips waren durchschnittlich nur 45% heil und 55% zerbrochen. Anführungszeichen oben aufgegessen haben die Neuntkläßler übrigens den Inhalt aller 16 testierten—bis auf den letzten Krümel. Die Skythen zwar Um ein weiteres kulinarisches Thema hat sich eine Gruppe der Sankt Johannes Schule bemüht: Tiefkühl Pizza. Untersucht wurden sowohl Markenprodukte von Wagner oder Ristorante als auch Discounter Pizzen von die DEL[,] Penny und die Rewe Hausmarke. Die zehn Tesla teilten die Salami Plätzen in kleine Stücke, damit alle Schüler und Schülerinnen Geschmack und Geruch beurteilen konnten. „Dabei hat sich gezeigt, dass die Pizza von Lidl sehr gut ankam [“, hat Bernward Neugebauer beobachtet. Geschmacklich bewerteten die Tester die Markenprodukte eher schlechter. Ein weiteres Kriterium war die Auftauzeit:] die Schüler gingen davon aus, dass ein Einkauf rund 30 Minuten dauert. Nach dieser Zeit haben Sie [die] Temperatur bei allen Pizzen gemessen und festgestellt [,] dass sie in jedem Fall über null Grad lag-d.h., dass man die Pizzen nicht wieder Einfrieren sondern so vorzubereiten sollte. Ein anderer Test untersuchte die abkühlt Zeit. Bernward Neugebauer: „Wir finden Pizzen unter 30° ungenießbar, daher haben wir auch diesen Aspekt untersucht.“ In dieser Kategorie hätten die Markenprodukte am längsten die Wärme gehalten. Am wenigsten überzeugte die Schüler die Penny Hausmarke: Der Teig sei ungleichmäßig dick, die Salamischeiben lagen alle auf einer Pizzaecke—und auch Geschmack und Geruch seien nicht ansprechend, urteilen die Zehntklässler.

10.3 Evaluation Sentence Error Rate : 12 correct out of 41 -> 29/41 = 70,73 % Word Error Rate: 73 errors out of 604 -> 73/604 = 12,09 % - Insertions: 2 + 8 falsely understood punctuation marks - Deletions: 19 words, 7 punctuation marks missing - Substitutions: 44 words by 55 words - Spelling errors: 13 10.4 Transcription by Siri (Substitutions are marked yellow, insertions purple, deletions green. Correctly transcripted words that are written in two words instead of one, with a capital letter instead of a small one or with ß instead of ss are underlined.) Schüler versuchen sich als Warentest da Von Britta Schlesselmann

10.5 Evaluation Sentence Error Rate: 6 correct out of 41 -> 35/41 = 85,37 % Word Error Rate: 110 errors out of 604 -> 110/604 = 18,21 % - Insertions: 0 - Deletions: 4 words - Substitutions: 106 words by 114 words - Spelling errors: 18 | |

|

|