|

Abstract

Based on my study of five experienced part-time translators of scientific texts from English to Malay and on the feedback obtained from fifty part-time translators in the field of science and technology using the think-aloud protocol (TAP) and questionnaire techniques, I have found the characteristics a competent translator must possess to ensure the effective knowledge transfer from one language to another. This paper discusses the characteristics of an effective translator in the transfer of knowledge. The researcher agrees with the definition of the translation process proposed by Bell (1991), Sager (1994) and Darwish (2003). The researcher is also of the opinion that the writing and translating processes share similar approaches and features, and a competent translator must be aware of this. Another finding from this study is that a competent translator must use Oxford's (1990) direct and indirect language-learning strategies while translating. Finally, the researcher will discuss her own model of translation which she feels a competent translator must adhere to.

Introduction

n this world of science and technology there is knowledge explosion every day. This knowledge which is generally written in the English language needs to be transmitted in various languages so that people who do not know how to speak and write the original langauge can get the knowledge necessary for industrial development and technological innovation to keep up with the rest of the world. To transmit this knowledge effectively, there is a need for competent translators in various languages. n this world of science and technology there is knowledge explosion every day. This knowledge which is generally written in the English language needs to be transmitted in various languages so that people who do not know how to speak and write the original langauge can get the knowledge necessary for industrial development and technological innovation to keep up with the rest of the world. To transmit this knowledge effectively, there is a need for competent translators in various languages.

Participants

The participants of this study were fifty-five experienced Malaysian part-time translators of scientific texts from English to Malay.

Methodology

Five of the participants who were from the University of Malaya participated in the think-aloud protocols followed by interviews. Another fifty participants came from universities, translation institutions, and colleges who completed the questionnaire.

Discussion of Findings

a. The Characteristics of an Effective Translator (one who practices translation)

From the questionnaire and interviews, the researcher reached to conclusion that for a translation to be accurate, clear, natural and effective, a translator must have the following characteristics:

- For a translator to translate scientific texts from English to Malay or between any other pair of languages, he or she must first of all be a subject specialist so that the content of the original text is communicated accurately, clearly and naturally. If the translator is a chemistry expert, then he or she should translate mainly chemistry texts rather than texts in other sciences, because this will ensure both quality and the speed of the translation.

- A translator must be very proficient in both the source and target languages. Mastery of the source language ensures that the meaning conveyed by the source text author is very clearly and accurately understood by the translator. Every aspect of it must be clearly interpreted by the translator. Mastery of the target language is even more important. A translated text is deemed weak if it is delivered in the target language poorly because the translator is not familiar with the grammar and nuances of the language. Thus, it is best if the target language is the translator's dominant or native language, because only such highly proficient language users will have the intuitiveness for the language and will thus be able to deliver a better translation.

- A translator must be familiar with the basic principles of translation theory and practice. A translator's job is not only to find equivalent terms in the target language with the help of terminology lists and dictionaries, but he or she must be able to deliver the translation according to the rules, style, and grammar of the target language so that the translation does not sound awkward and unnatural. The translated version must be delivered in a manner that sounds natural and smooth-flowing and is meaningful to the target reader. According to Ainon Muhammad (1979:12), an author on translation, a good translator must be a subject specialist, be good in the source language, even better at the target language, and must have received training in translation theory and practice. The researcher would like to add that if a translator wishes to translate scientific texts, then he or she must also receive science training. About 84% of the translators in this study were Malays, and they confirmed the fact that it is an advantage for them to be able to translate into their own mother tongue, because they know how the language ought to be written and how it should sound.

- A good translator must have empathy for his or her target readers. He or she must ensure that the translated product is appropriate to the intelligence and proficiency levels of the target reader. A text translated for primary school students must cater to their intelligence and language proficiency level, and a text translated for university students must be suited to their level of comprehension. Once the translated text fulfils these criteria, the target readers will find it easy to follow the concepts, processes and other ideas expressed in the translated text and these reader-friendly translated texts help achieve the commercial or other purpose of the translation. In other words, translators must know the skopos or purpose of their translation task.

- A translator must be committed and disciplined. The translation task commissioned to him or her must be completed by the deadline given so that the information that is translated does not become outdated and the user of the translation is properly served.

- A good translator must be aware of the culture of both the source and target language readers. In this way, he or she will be able to translate to the target language based on the culture of the target readers and thus facilitate the reading and understanding of the translated text by the target readers.

- An effective translator must learn to divide the workload among his colleagues who are subject specialists when translating voluminous academic books or long documents in the field of science and technology so that the process of translation can be speeded up and thus the readers are updated with the latest in these fields.

- An effective translator should have all the necessary translation tools such as monolingual, bilingual and subject dictionaries, thesauri, terminology lists, a computer, a printer etc. available while translating so that no time is wasted searching for them while translating.

- A translator must be aware of the whole translation process so that he or she will be able to translate quickly, accurately, clearly and naturally to the target language. Robinson (1997:49) has proposed that the translator is a learner and he suggests that "translation is an intelligent activity involving complex processes of conscious and unconscious learning." The researcher agrees with his proposal and also with the statement that translation is basically a problem-solving task. Robinson (1997:51) suggests that "translation is an intelligent activity, requiring creative problem-solving in novel, textual, social, and cultural conditions." A translator should know that translation is a learning activity and it involves the use of the main direct (memory, cognitive and compensation) and indirect (metacognitive, affective and social) language-learning strategies proposed by Oxford (1990). A translator who uses these strategies will be able to perform a good translation.

- An effective translator must be aware that writing and translating involve similar features. The writing stages involve determining the message content (what?) and general purpose of the message (why?), defining the recipients (who?) and function (expected reaction of the recipients), planning the amount and order of content (What is assumed) and the realisation (what is expressed linguistically and what by some other means). The preparatory phase for writing involves the choice of text type (letter, novel, literary, non-literary, expository, informative, argumentative etc.). Here the writer must consider the format, publication, circulation, presentation involving the questions—where?, when? how? and the writer also must consider the alternative modes of communication. In addition to considering the above, the writer, according to Sager (1994:186), also must determine the structure, division of the written material into chapters, headings and paragraphs. This will lead to the message production. Sager (1994:186) suggests that the writer must evaluate, revise, modify and finally present his written work for publication. Like writing, translating too involves these stages—identification of the SL document, identification of intention, interpretation of specification and cursory reading and choice of TL text type and the other preparatory activities as in writing and original work. The researcher agrees with Sager's (1994) suggestion that writing and translation share similar features. In fact, the researcher is of the opinion that of the four skills in language learning, writing seems to come closest to translation. The researcher also agrees with Smith-Worthington and Jefferson (2005:80) in that the process of writing involves planning (prewriting, shaping, researching), drafting, revising and copy-editing (proofreading and publishing). She also agrees with Smith-Worthington and Jefferson's (2005:84) suggestion that the three features of writing are as follows:

- Writing is recursive or circular in nature—it is a backward and forward process. The recursive nature means that the thinking process sometimes circles back to earlier stages.

- Writing takes time—time is needed for ideas to emerge and develop. Different stages have their own activities. It takes sufficient time to complete a document.

- Writing is different for everyone—it varies from one person to the next. This is because people are different, their thinking processes and learning styles vary. A person writes to fit his or her personality and thinking style.

- A good translator must be aware of the importance of cognitive information processing of texts so that they can be accurately understood, processed and transformed by their cognitive system.

- Based on the researcher's experience as a translator, on her discussions with other translators, and on this research, the researcher strongly feels that the above writing processes and the three features of writing put forward by Smith-Worthington and Jefferson (2005) can be extended to the process of translation. Here too we see a close parallelism between writing and translating because they share similar features and approaches.

b. The Process of Translation

A competent translator must be aware of the process of translation to make effective knowledge transfer from one language to another possible. From the feedback obtained from the five participants who took part in the think-aloud protocols and interviews, the researcher discovered that the main direct and indirect strategies proposed by Oxford (1990) were used by them while translating. These strategies are shown in Table 1 on the next page. From the TAPs analysis using the inductive method, the researcher matched her analysis of the TAPs transcriptions to Oxford's (1990) Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL) and found three additional strategies used by the participants which were not present in Oxford's SILL. The new findings comprise one metacognitive and two cognitive strategies. The three new strategies comprise the following:

1. Stating one's own beliefs on how to translate and giving the reasons supporting them (metacognitive strategy).

From this research, it was apparent that the participants had their own mindset or schema about how to go about translating. They verbalized aloud this preconception or design of the expected completed version or virtual blueprint of their translated product. While translating they reminded themselves that they should abide by these beliefs which were arrived at from past experience and translation training. Some examples include:

- "Now that I know the meaning in my head, I shall translate it using my own words in Malay so that the original meaning is not lost. I do not believe in and do not practice word-for-word translation. I prefer understanding first before translating," and

- "I don't translate word-for-word. Being a Malay, I have language intuitiveness and upon further reading, I always refine my translated work."

Table 1

OXFORD'S STRATEGY INVENTORY FOR LANGUAGE LEARNING (SILL)

|

DIRECT STRATEGIES

|

INDIRECT STRATEGIES |

|

1. Memory Strategies

- Creating mental linkages

(e.g. grouping, associating, elaborating)

- Applying images and sounds

(e.g. using imagery, semantic mapping)

- Reviewing thoroughly (structured reviewing)

- Employing action

(e.g. using physical response or sensation)

2. Cognitive Strategies

- Practicing (repeating, formally practicing with sounds and writing systems, recognising and using formulas and patterns, recombining and practicing naturalistically.

- Receiving and sending messages

(getting the idea quickly, using resources for receiving and sending messages.)

- Analysing and reasoning (reasoning deductively, analysing expressions, analysing contrastively (across languages), translating, transferring)

- Creating structure for input and output (taking notes, summarising, highlighting)

3. Compensation Strategies

- Guessing intelligently (using linguistic clues, using other clues)

- Overcoming limitations in speaking and writing (switching to the mother tongue, getting help, using mime or gesture, avoiding communication partially or totally, selecting the topic, adjusting or approximating the message, coining words, using a circumlocution or synonym)

|

1. Metacognitive Strategies

- Centering your learning (overviewing and linking with already known material, paying attention, delaying speech production to focus on listening)

- Arranging and planning (finding out about language, organising, setting goals and objectives, identifying the purpose of a language task, planning for a language task, seeking practice opportunities)

- Evaluating (self-monitoring, self—evaluating)

2. Affective Strategies

- Lowering your anxiety (using progressive relaxation, deep breathing or meditation, using music, using laughter)

- Encouraging yourself (making positive statements, taking risks wisely, rewarding yourself)

- Taking your emotional temperature (listening to your body, using a checklist, writing a language learning diary, discussing your feelings with someone else)

3. Social Strategies

- Asking questions (asking for clarification or verification, asking for correction)

- Cooperating with others (cooperating with peers, cooperating with proficient users of the language)

- Empathising with others (developing cultural understanding, becoming aware of others' thoughts and feelings)

|

Source: Oxford (1990). Language Learning Strategies—What Every Teacher Should Know.

New York:Newbury House Publishers

- Finding one's own solutions to the problems identified and carrying them out (cognitive strategy)

Problem identification comes under the metacognitive strategy, but here, the participants moved one step forward. They used cognitive strategies to solve their problem. All five participants, using the TAP technique, found that some sentences in the English language scientific texts were very long and confusing, and found such complex sentences very difficult to translate into the Malay language, which has a different pattern of grammar. If they were to maintain the complex sentences in the Malay translation, the target readers might become confused. In an effort to overcome this problem, they found a solution. They decided to divide the complex sentences into two shorter sentences for easier analysis and comprehension. In this way, the translation process became more manageable and simpler. The meaning was communicated much more easily and accurately and the participants were satisfied with their completed translated version in the Malay language.

- Using the discrimination strategy to choose the closest equivalent term from two or three alternatives identified in the target language based on the context of the situation (contextual meaning) and the culture of the target readers (cognitive strategy).

A word may have many meanings in different situations, so, the participants had to decide on choosing the most appropriate equivalent terms in their translation for the terms given in the English-language scientific source text. For this, they had to choose from a number of alternatives identified, using the discrimination strategy. The equivalent term which is finally chosen was also based on the context of the situation or contextual meaning of the text and the culture of the target readers, so that the target readers of their translated versions would not get confused. Some examples taken from the TAPs analysis of the five cases are as follows:

- For the word "responsible", the participant had to decide between the two terms

tanggungjawab and berperanan; she chose berperanan as it suited the scientific context, whereas tanggungjawab is used for people in a social sense.

-

For "emotional response", the participant had to choose between

gerakbalas or tindakbalas; she chose the former as it suited the context of the situation or the contextual meaning of the text, whereas the latter is used in the context of a chemical reaction and was thus not suited to the text.

c. Translation Strategies Used by the Participants

A competent translator must be able to use translation strategies while translating from the source language to the target language. To investigate the translation strategies used by the five participants in this study, the researcher first analysed the transcripts of the TAPs and then mapped them on to Oxford's (1990) SILL to find out whether SILL was used by them and also to find out the other strategies used which were not given in Oxford's (1990) SILL. The strategies used by the five case studies as mapped on to Oxford's (1990) SILL model is presented in Table 2. The participants who had more time translated two texts while those who were pressed for time only agreed to translate one text aloud. The strategies marked with an asterisk and highlighted are the additional strategies found by the researcher in this study. The key to Table 2 is explained in the box below.

|

KEY to Table 2

The first two columns represent the number and types of strategies used, that is both the direct and indirect strategies and the remaining five columns in Table 2 represent the cases while the rows represent the types of strategies used. A tick was put in the column next to the strategy if the strategy was used by the participants for this study, while a cross was put if the strategy was not used by them. The strategies used which are marked with an asterisk mark and bolded are the additional strategies found from this study of the process of translating scientific texts from English to Malay. |

TABLE 2

The Strategies Used by the Participants in their TAPs

|

Strategies Used by Participants In This Study |

Case 1

- One Text |

Case 2

- Two Texts |

Case 3

-One Text |

Case

4

-Two Texts |

Case

5

- One Text |

|

No. |

DIRECT STRATEGIES |

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

Memory Strategies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. |

Using imagery |

/ |

/ |

x |

/ |

x |

|

2. |

Reviewing |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

x |

|

B |

Cognitive Strategies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. |

Reading and comprehension |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

2. |

Summarising |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

3. |

Highlighting |

/ |

x |

x |

/ |

x |

|

4. |

Analysing and Reasoning—translating |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

5. |

* Choosing equivalent terms based on the contextual meaning in the text (situation) and the culture of the target readers by using the discrimination strategy to choose the closest equivalent term in the target language from two or three alternatives identified. |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

6. |

Academic Elaboration |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

x |

|

7. |

* Finding their own solutions to the translation problems and carrying them out. |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

8. |

Repetition |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

9. |

Resourcing |

x |

x |

x |

/ |

x |

|

C. |

Compensation Strategies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

Overcoming limitation in writing: paraphrasing |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

2. |

Overcoming limitations in writing: switching to the source language. |

x |

x |

x |

/ |

x |

|

II |

INDIRECT STRATEGIES |

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

Metacognitive Strategies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. |

Planning and organisation—Making decisions |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

2. |

Selective attention—attending to one sentence at a time. |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

3. |

* Stating one's own beliefs on how to translate—giving reasons supporting those beliefs and implementing them. |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

4. |

Problem Identification |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

5. |

Comprehension monitoring |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

6. |

Ability evaluation |

/ |

/ |

x |

/ |

x |

|

7. |

Self-monitoring/Production monitoring |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

8. |

Performance evaluation |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

x |

|

B |

Affective Strategies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. |

Encouraging yourself: Marking verbally the end of a paragraph and end of a task. |

x |

x |

x |

/ |

/ |

|

C. |

Social Strategies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. |

Empathising with others |

/ |

x |

x |

/ |

x |

|

2. |

Asking questions |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

x |

d. Researcher's Proposed Translation Model

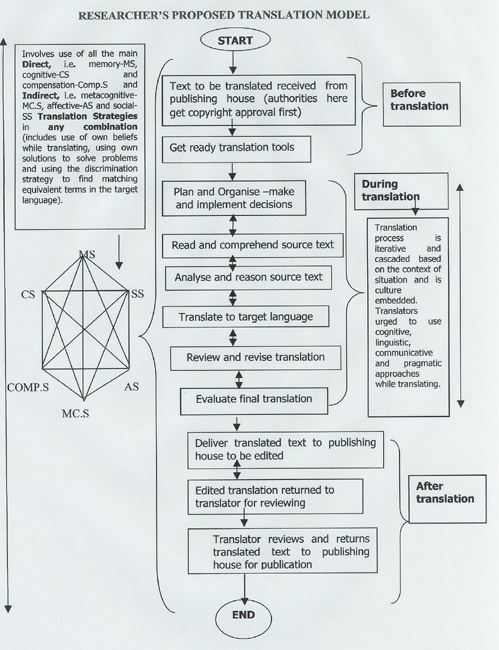

External processes of translation are situation-specific inasmuch as internal processes are unique to the individual. Based on the findings obtained from the internal translation process and the external factors involved in translation, the researcher has proposed a translation model which is shown in Figure 1. This translation model is divided into three phases: before, during and after the translation process and these are discussed below.

1. Before Translation: Here, the authorities at the publishing house apply and obtain the copyright approval for translating a chosen English-language science book to the Malay language. Then the prospective translator, who is a subject specialist is chosen. A contract is signed between the publishing house and the translator. A deadline is given to the translator to complete his or her translation task. If the chosen translator feels that he or she cannot complete the translation on a part-time basis, he or she is free to divide the chapters among his or her colleagues who are also subject specialists, but he or she must supervise their translation to ensure that there is uniformity and consistency of the terms used in the translated text. The translator gets his translation tools such as the bilingual and monolingual dictionaries, writing tools or computer, thesauruses, terminology lists etc. ready.

2. During Translation/Internal Translation Process. In this stage, the translator plans and organises his or her translation, that is, makes and implements decisions. First, the translator decides to read and comprehend the source language scientific text. Then he or she actually reads the text and summarises it. Next, he or she analyses the difficult keywords and phrases, paraphrases them and tries to find the most appropriate equivalent terms from two or three options identified in the target language which best suit the context of the situation of the scientific text and the culture of the target readers. Then he or she translates the source language scientific text sentence by sentence into the target language. Monitoring is also done after completing the translation of each sentence. Revision is done if deemed necessary. Then the translator evaluates his or her whole performance of the whole completed translated version against the original scientific text in the source language. Then he or she gives his or her colleagues to read the translated version for reviewing purposes and makes the necessary changes if necessary.

Figure 1

3. After Translation. Here the proofread translated text is submitted to the publication house for editing. Once the editors at the publication house have edited the translated text, it is returned to the translator who reads it again to ensure that the content has not been distorted or made ambiguous. Once the translator is satisfied with the translated and edited text, it is returned to the publication house for publishing. If there are any issues with the editing performed by the editors at the publishing house, then these are discussed between the parties. Once both parties have reached a consensus regarding the revision, the translated text is published and then marketed.

From the translation model depicted by the researcher in Figure 2, it is apparent that the translator starts the internal translation process by planning and organising, followed by reading and comprehension, analysing the source text information, translating, monitoring and evaluating his or her own performance.

The longer two-headed arrow on the left shows that the translation strategies, comprising the main direct and indirect language strategies and the three translation strategies found from this study are used from the start to the end of the translation process. The six-sided diagram shows that the translation strategies are flexible and can be used in any combination, for example metacognitive with social, social with compensation, cognitive with affective etc.

The shorter two-headed arrow on the right in Figure 2 of the proposed translation model shows that the internal translation process is iterative, cumulative and integrative. It also shows that while translating the translators use all the four approaches: cognitive, linguistic, communicative and pragmatic to ensure that the final translated version suits the culture, intelligence, context of situation and language proficiency level of the target readers of the translated version. In other words, the researcher suggests that the skopos or purpose of the translation must be emphasised. Furthermore, the translation process is iterative and cascaded, that is, it involves forward and backward-looking activities. In addition, translators often review and revise their work while translating. A final evaluation is done upon completing the whole translation task.

This proposed translation model by the researcher is derived from the findings from this study. It is open to further research by future researchers in the field of translation who can experiment it with other kinds of texts or text-types and with other pairs of languages in the world.

Conclusion

In brief, in order to be a competent and reliable translator in transferring knowledge effectively from one language to another, the researcher believes that a translator should try his or her best to acquire the characteristics of a competent translator as presented in this paper. Also, a competent translator should be familiar with the translation process and the translation strategies that need to be used while translating. Finally, the translation model proposed by the researcher can be used as a guide to achieve a good translation.

References

Ainon Muhammad. (1979). Pengantar Terjemahan. Kuala Lumpur: Adabi.

Bell, R.T. (1991). Translation and Translating. London: Longman.

Danks, Joseph H. et al. 1997. Cognitive Processes in Translation and Interpreting. Applied Psychology: Volume 3. London: Sage Publications.

Darwish, A. (2003). The Transfer Factor—Selected Essays on Translation and Cross-Cultural Communication. Melbourne: Writescope Pty Ltd.

Kulwindr Kaur a/p Gurdial Singh. (2003). A Study of the Process of Translating Scientific Texts from English into Malay. PhD Unpublished Thesis. University of Malaya.

Newmark, P. (1988). A Textbook of Translation. Hertfordshire: Prentice-Hall.

Oxford, R.L. (1990). Language Learning Strategies—What Every Teacher Should Know. New York: Newbury House Publishes.

Robinson, D. (1997). Becoming a Translator: An Accelerated Course. London: Routledge.

Sager, J.C. (1994). Language Engineering and Translation: Consequences of Automation. Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Smith-Worthington and Jefferson. (2005). Technical Writing for Success. USA:Thomson South-Western.

|